Notes on Quotes

Wedgwood Pottery: Finding the Lost Ayoree Cherokee Indian Mine (A Historical 1767 Wedgwood Trip from Charles Towne)

By Gordon Mercer and Marcia Gaines Mercer

“The Indians set a high value on their white earth: however I sent for a linguist, and after strong talk which lasted near four hours, we settled matters….” Thomas Griffiths, 1767

It was 1987 and we were riding our horses along highway 28, when we first saw the marker: “Wedgwood….several tons of clay taken on 1767 from a nearby pit by Thomas Griffiths…..” Intrigued, we talked about someday visiting the white clay mine. We didn’t know finding the mine would not be easy and we did not know research would lead us to the early Charleston, SC planter, Thomas Griffiths.

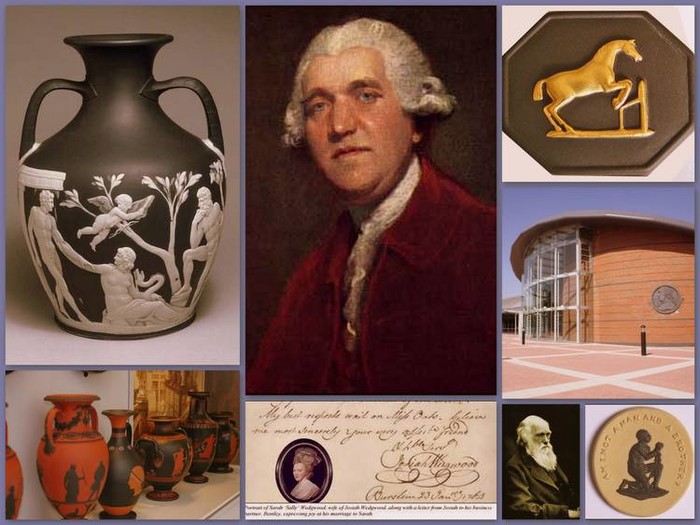

English potter and designer, Josiah Wedgwood, dreamed of manufacturing the best pottery in the world. His unique glazes and classical designs drew heavily from the Roman and Greek periods. Orders poured in from the rich and royal. Empress Catherine and Queen Charlotte were customers, and Wedgewood labeled one of his lines, “Queens Ware.” He found the best Kaolin clay came from a Cherokee mine in fabled Ayoree, which would later become, Franklin, NC. “White Unaker,” the clay was called and it revolutionized Wedgwood pottery. Josiah Wedgwood had to find a way to get 5 tons of it from North Carolina to Wedgwood Pottery in England.

He commissioned Thomas Griffiths, a Charles Towne area planter, for the mission of going from Charles Towne to Ayoree and returning to England with the 5 tons of the rare clay. Griffiths kept a journal of the 1767-1768 journey. He endured many hardships including thieves, treacherous trails, lame horses and a dangerous horse slide down an icy mountain, which he barely survived by clinging to a tree. Along the trail he teamed up with a captured Cherokee woman and helped return her to her Cherokee relatives.

Russell Townsend, Tribal Historic Preservation Officer for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, explained the importance of Kaolin clay to the Cherokee in 1767. It was used, he told us, for game tiles, tobacco pipe production and as slurry for the interior and exterior of homes. Mica deposits nearby meant mica frequently got into the slurry mix. The mica made the Cherokee homes sparkle like diamonds.

There is disagreement about the original location of the Cherokee Kaolin mine but most think it to be in the Iotla area in Macon County, North Carolina. After studying maps and talking to those with extensive family history in Macon County, Gordon located a disabled veteran, whose relatives had worked the mine. Following the veteran’s directions, Gordon found himself at Jerry Anselmo’s place, “Great Smoky Mountain Fish Camp and Safari’s” on the Little Tennessee River. Anselmo became aware of the kaolin mine on his property when he moved to Franklin 22 years ago. Thomas Rickman of historical Rickman’s store told him it was the original Cherokee mine and the source of Kaolin for early Wedgwood pottery.

Jerry drove us near the mine site in his jeep and we hiked the remaining distance. Large quartz boulders line the way and stand at the entrance of the mining area. We were enchanted by the white clay cliffs and ground sparkling with mica and Kaolin. It was a perfect Indiana Jones movie setting.

Jerry Anselmo is a gracious host and we were impressed with his conservation orientation. Before moving to Franklin, he worked with Jacques Cousteau on the Save the Dolphins Project. Did we find the lost mine? We think we did.

Waterford Wedgwood went bankrupt in 2009 as sales dropped in the economic downturn. It was bought out by KPS Capital Partners and reorganized as Waterford Wedgwood Royal Doulton. Josiah Wedgwood was an experimenter, artistic designer and had a daring determination to produce the world’s finest pottery. We feel certain his legacy will survive.

* For more information, Barbara McRae’s extensive and important research on Franklin’s Kaolin clay history and links to Wedgwood Pottery can be found at the Franklin, North Carolina Historical Museum. She is editor of “The Franklin Press.”

Gordon Mercer is on the Board of Trustees of Pi Gamma Mu International Honor Society. He is professor emeritus at Western Carolina University and a published author. Marcia Gaines Mercer is a writer and published author. We love Charleston and have a place in nearby Garden City.